Issue No. 4

After the Family: reinventing home, ownership, inheritance

Could new definitions of the family help address inequalities in the next urban era?

Unfold, Issue No. 4

After the Family

Today's family structure could redefine our relationships to home, ownership, and inheritance.

We don’t think about it often, but the idea of family is in constant evolution.

Despite new definitions of family proliferating and becoming dominant models, we continue to live in a built environment that was largely designed for a single specific model: the traditional mononuclear family.

In this edition of Unfold, we explore how new definitions of family could drive us to reinvent our conception of home and our relationships to ownership and inheritance.

—

Both the Extended and Nuclear family models responded to economic conditions to become the most common models of their times.

Extended: 18th, 19th century

Nuclear: 1950 - 1965

Today, single people represent 28% of all US households, which makes this group more common than any other domestic unit, including the nuclear family.1 Since the 1950’s, the mononuclear family model has been engraved in our minds: a married couple living with two and a half kids in a standardized home that the husband buys and the wife maintains. Yet today, we are witnessing the end of this traditional model. For example in Paris, the proportion of children living in single-parent homes is 28%.2 In Munich, mononuclear families fell below 14% in 2015; and more and more major cities are falling below that rate each year.3

With ever-changing social and demographic conditions comes new forms of relationships. Divorce rates are hitting all-time highs: almost 50% on average across Europe and 89% in Luxembourg.4 In the US, more than 40% of new mothers are unmarried.5 Back in the 1950s, only 27% of marriages ended in divorce; now we have a 50% divorce rate for first marriages and 65% the second time around.6 In France, the proportion of women married at 25 dropped from 78% to 10% in the last half century. For men, that rate fell from 63% to 5%.7 For relationship specialist and psychotherapist Esther Perel, “Today, we turn to one person to provide what an entire village once did: a sense of grounding, meaning, and continuity. At the same time, we expect our committed relationships to be romantic as well as emotionally and sexually fulfilling. Is it any wonder that so many relationships crumble under the weight of it all?”8

Today, we turn to one person to provide what an entire village once did. Is it any wonder that so many relationships crumble under the weight of it all?

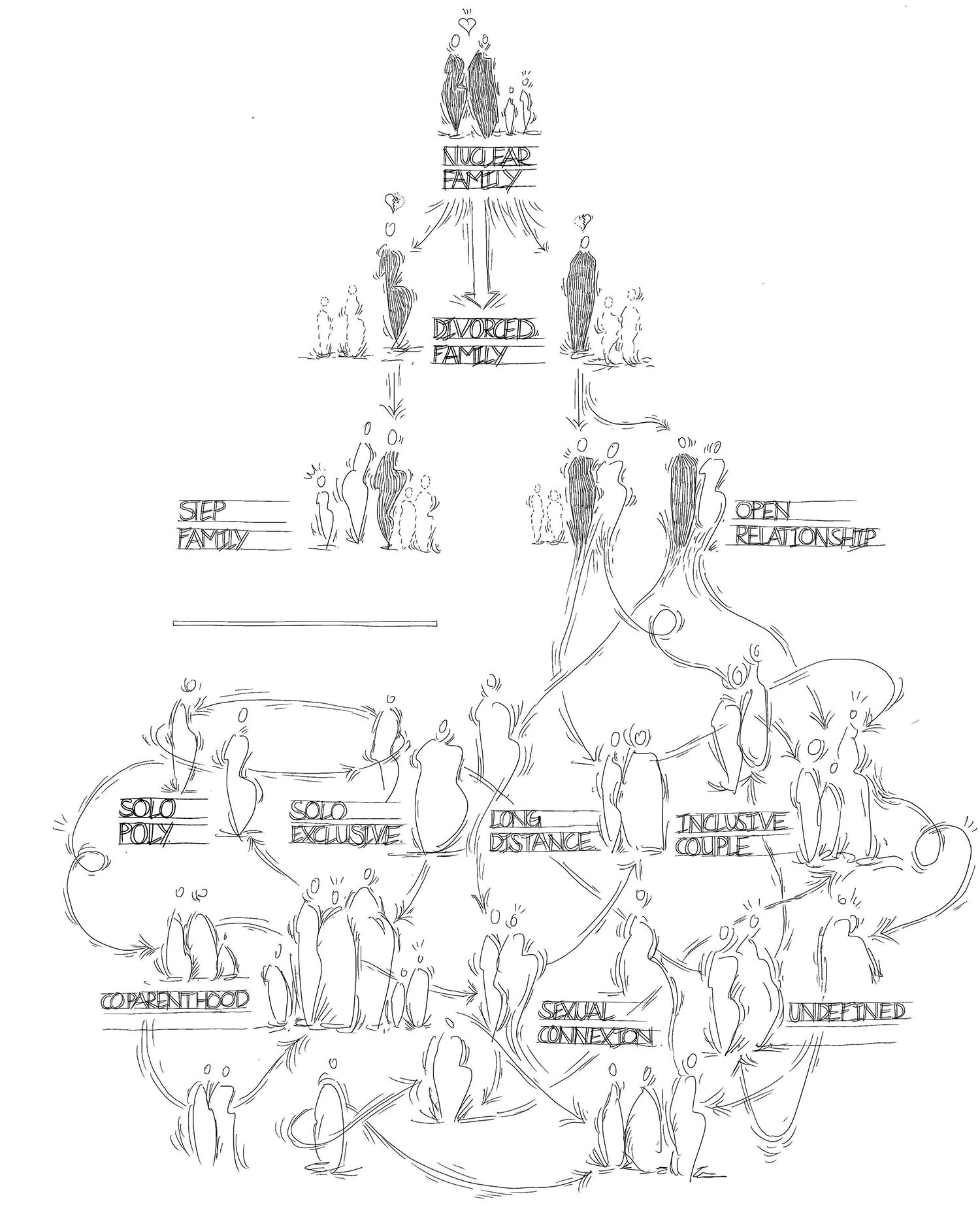

In place of the traditional models, we are seeing an explosion of new kinds of relationships and experimental bonds. We are shifting from a pre-packaged, static definition of relationships into dynamic territories of co-created new models of relationships. Standard monogamous frameworks are still in play, but for example in the US, over 20% of people have attempted some form of non-monogamy at some point in their lives.9 New bonds like step-parenting, blended families, long-distance, polyamory, open relationships, etc... are being pioneered. “Our partner's sexuality does not belong to us. It isn't just for and about us, and we should not assume that it rightfully falls within our jurisdiction,” Perel notes. This even goes beyond traditional understandings of heterosexual and homosexual couples to explore a multiplicity of gender and relationship dynamisms. Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman synthesized it all: “We are opening an era of Liquid Love.”10

—

Singles and Chosen Families are the new emerging standard models today.

Most of our history, we have structured into groups as Extended Families. As sociologist David Brooks describes, “There were uncles, nieces, nephews around. If a relationship failed or if someone died, there was plenty of other people to pick up the slack. During the Victorian era, the numbers of members was higher than ever before and ever since. The world that people knew was falling apart and they felt economically threatened.”11 In the industrial era, people left their big family farms for cities. Entire households could be supported by the lone income of a father in a factory, creating perfect conditions for nuclear families to thrive. This model is still clear in our minds today, yet these conditions have fundamentally changed.

So what is the family today? We are seeing the emergence of the Chosen Family. These kinds of non-blood-related bonds first appeared in gay communities in San Fransisco in the eighties.12 Individuals who were cast out by their biological parents came together and chose to function as a unified family. This ‘chosen’ quality quickly expanding beyond the gay community as well; economic conditions are increasingly threatening to more and more people. It appears we are trying to reinvent a modern version of the extended family, only more dynamic and increasingly networked: One’s ‘family' is no longer exclusive to bloodlines. The way a family is formed is more by individual choices, economic constraints, and life accidents than affiliation or genealogy. As Brooks points, “tragedy and suffering have pushed people together in a way that goes deeper than just a convenient living arrangement. They become Fictive Kin.”11

—

Family structure can shift and evolve through many definitions over one's full life.

The traditional family is becoming the Chosen Family, yet the way we build and design homes continues to reflect a century-old lifestyle. Today’s built environments were conceived for mononuclear families, yet we now live in a society of polynuclear families. Brooks goes on: “We are at a moment of cultural lag. We have an old and archaic idea of what is a family. And it has existed only in this freakish moment between 1950 and 1965.”11 The home as we know it is not yet suited to embrace these new models of family in the making. Rather than architecture and urbanization being tailored to fit new family units, people are left to appropriate homes designed for an outdated lifestyle.

What should the home be today? How can our habitats adapt to accompany and fit these highly dynamic, diverse new forms of relationships?

Homes today should be designed for 1) collective living to create resilience from threatening economic conditions, 2) intergenerational bonds to integrate the full spectrum of the chosen family, and 3) adaptable spaces to support ever-changing lifestyles and relationship dynamics.

We are only just beginning to see new experiments emerge in flexible and shared living spaces – modern prototypes in cohabitation that explore the question of what is shared habitat today. Until now, we have only understood home in terms of productive young professionals and reproductive family units; how can we be more inclusive of seniors as a part of our chosen families?

It's time we design shared homes to cultivate new forms of resilience and find unexpected complementarities from cross-generational cooperation. Isolation of our elders has become the cultural norm. In 1940, 25% of Americans lived in multigenerational homes. By 1980, this figure plummeted to only 12%.13 In the UK, 43% of people over 65 often feel disconnected from their families or sense of community.14 And in the US, 4 out of 10 seniors have minimal or no contact with their children.15 If we only understand home in terms of productive young professionals or reproductive family units, how can we be more inclusive of seniors as a part of our chosen families?

With the rise of the Chosen Family, our relationship to ownership may also evolve. Millennials are famously the first generation in history to earn less than their parents at the same age. In the US, they are less than half as likely to own a home and, as a generation, are 1 trillion dollars in debt.16 In response to these incredible constraints, there have been a lot of inventive experiments around access and ownership emerging within the cohabitation movement.

New prototype models of cohabitation and rent-to-own are coming. We are already seeing space as a service with the rise of co-spaces in cities, but if we go beyond this, new relationships between access and ownership are following. Typically, paying rent for space is a financial drain. Rent is generally more flexible and affordable than paying loans, but ultimately the money is lost, not invested. Rent-to-own is a hybrid model that first appeared in housing contracts. Renters can afford to move in immediately, while a percent of the payment is invested directly into ownership of the property. At the end of the rental agreement, renters have an option to purchase “the rest” of the home's equity. This has been largely exclusive to rural and suburban houses, however, we are beginning to see it shift and make its first trials in shared urban living.

—

Can shared living concepts pioneer a new era of rent-to-own? Sketch: Cohabitation Unit, project by Cutwork.

Transmission of home ownership is deepening systemic inequality. Division of wealth has grown significantly all over the world, especially concerning real estate property. In the United States in 1980, the top 1% of the biggest property holders owned 22% of all private land. By 2014, they owned 39%.18 In 1973 France, 34% of young households (between 25 and 44 years old) owned their home. By 2013, this dropped to only 16%.19

The economist Thomas Piketty points that as of 2020, the top 10% of the wealthiest individuals owned over 55% of available private property around the world, while the poorest 50% didn’t own any.20 Home ownership is one of the most reliable keys to bridging the inequality gap, yet the bar to be able to do so has only gone up. Buying a home as a single is not the same as buying a home as a couple – and of course, not the same as inheriting it. Brooks notes, “Affluent people can still afford the nuclear family and homes. For poor people, with divorce rates still on the rise, this model can been economically catastrophic.”12

—

Blood lineage used to transfer political power. Today it still transfers economic power.

Is this for the best?

The traditional family has been the place of transmission of beliefs, culture, knowledge, but also social status, money and privileges. Inherent to our traditional understanding of home is that fact that it is a place transmitted by our parents. What if we realized that the underlying principles and mechanisms of cohabitation and shared spaces could also be applied to our understanding of inheritance? There is a lot of inertia in this inherited transmission of economic power, and it is fueling systemic inequality, as children of wealthy parents can build on that inheritance and children of poorer parents are often in greater debt to begin with. Western society is very proud to have replaced kings and monarchies with democracy – to place political power and choice in the hands of the collective, rather than it being privileged and exclusive to bloodlines. Yet, we still enable economic power and wealth to pass and consolidate through descendant’s inheritance.

The top 10% of the wealthiest individuals own over 55% of available private property around the world. The poorest 50% didn’t own any.

What if we build the emerging chosen family model around an idea of ‘collective inheritance’? Each year in France, roughly 250 billion euros are transferred through inheritance. The wealthiest 10% of the population inherit 52% of this sum. The bottom 50% take only 7%.21 If we evenly redistributed this collective amount to each person who turned 18 that year, each person would receive 310,000 euros.21 Imagine even if a smaller fraction were redistributed this way how significant it could be to bridge the equality gap. After all, we are already exploring new forms of ownership with shared habitat, rent-to-own contracts, and access economy.

—

Shifting from familial transfer of wealth to collective transfer would mean €310,000 to each person who turns 18 each year in France.

Perhaps in 200 years, we’ll look back to see how narrow and unequal our understanding of family was in the 20th century, just as we do now looking back at traditional victorian lifestyles. The emergence of the chosen family is an opportunity to rethink our homes to accommodate any number of diverse relationships that can co-exist across generations and within one’s full life. Beyond this, chosen families could reflect a deeper change to rethink our relationships to ownership and inheritance.

The key to truly addressing inequalities today is in redesigning transference of wealth and inheritance; home ownership and family structure are at the heart of this issue. If we extend this thinking with the chosen family becoming a standard model and build a society less upon blood lineage, housing could become a universal birth right – along with the basic rights to health care, income, mobility, and education. Anyway, shouldn't our natural trajectory move towards more and more systemic collective resilience?

The family structure we’ve held up as the cultural ideal for the past half century has been a catastrophe for many. It’s time to figure out better ways to live together.11

— David Brooks

Sociologist, Author

Edition

Unfold is a pocket-size, one-page magazine full of ideas for today’s living.

Every other week, one A4, one topic – from the perspectives of designers, inventors, sociologists, and architects.

By architecture and design studio CUTWORK.

Writers

Bryce Willem, Antonin Yuji Maeno, Léa Brosseau

Images

Cutwork, sketches by Antonin Yuji Maeno

Published

September 22, 2020

Sources

-

1

“US Census Bureau Releases 2018 Families and Living Arrangements Tables.” United States Census Bureau, November 14, 2018. Link.

2

Algava, Élisabeth, et all. "In 2018, 4 million children under 18 live with only one of their parents at home." The French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies, January 14, 2020. Link.

3

Maak, Niklas. Living Complex: From Zombie City to the New Communal. Munich: Hirmer Publishers, 2015. Purchase Book.

4

“Divorce rates in Europe in 2019, by country.” Statista, July 27, 2022. Link.

5

Livingston, Gretchen. “The changing profile of unmarried parents.” Pew Research Center, August 25, 2018. Link.

6

Miller, Claire Cain. “The divorce surge is over, but the myth lives on.” The New York Times, December 2, 2014. Link.

7

“Legal marital status of people by sex, Annual data from 2006 to 2018.” Institut National de la astatistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE), January 15, 2019. Link.

8

Perel, Esther. Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence. Harper, 2007. Purchase Book.

9

Haupert, Mara L., Gesselman, Amanda N., et all. “Prevalence of experiences with consensual nonmonogamous relationships: Findings from two national samples of single Americans.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy: vol. 43, p. 424-440, 2017. Purchase Issue.

10

Bauman, Zygmunt. The Liquid Life. Polity, June 24, 2005. Link.

11

Brooks, David. “The nuclear family was a mistake.” The Atlantic, March, 2020. Link.

12

Brooks, David. “How the Nuclear Family Broke Down.” The Atlantic, February 10, 2020. Link.

13

Roberts, Sam. “Report finds shift toward extended families.” The New York Times, March 18, 2010. Link.

14

Davidson, Susan and Rossall, Phil. “Age UK Loneliness Evidence Review.” Age UK, July, 2015. Link.

15

Ro, Christine. “The truth about family estrangement.” BBC, April 1, 2019. Link.

16

Riche, Robert. “Four Reasons Why Millennials Don’t Have Any Money with Robert Reich.” January 7, 2020. Link.

17

Lacko, James M. and McKernan, Signe-Mary, et all. “Survey of Rent-to-Own Customers.” The US Federal Trade Commission, April 2000. Link.

18

Alvaredo, Facundo and Chancel, Lucas, et all. “World Inequality Report 2018.” World Inequality Lab, 2018. Link.

19

Laferrère, Anne and Pouliquen, Erwan, et all. “Housing Conditions in France, 2017 Edition.” Institut National de la astatistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE), 2017. Link.

20

Piketty, Thomas. The Economics of Inequality. Harvard University Press, 2015. Link.

21

Ballufier, Asia.“Should we remove the inheritance (or increase the inheritance costs)?” Le Monde, February 5, 2020. Link.